Conversation with Mohammed Laouli

Karima Boudou : You studied Philosophy at the University in Rabat, what did you do afterwards?

Mohammed Laouli : At the time in 1990, I was creating without really understanding what art was. The first thing I did was to write on the front doors of the high school: Life is hard but we’ll resist. I wrote it but had no notion of street art; it was a spontaneous action after having found a phrase. I was a little manipulated by the fact that I spoke English and by the Americanism that invaded Morocco with “smurf” (Smurf and breakdancing are the dance elements of the larger movement of hip-hop. Hip-hop is a popular culture that came from poor neighborhoods in the United States at the end of the 1980s. It rapidly spread in Europe and in Morocco during the 1980s. From its appearance in the West, young Moroccans living in Europe brought rap to Morocco during their season returns by way of tape cassettes in their suitcases. During the mid-90’s, artistic spaces like the Cage began organizing dance competitions. Until 1999, almost all the groups rapped in English, which was followed by the birth of rap in Darija and the development of new technologies that allowed the democratization of rap in Morocco. Moroccan rappers took several years to transform American rap into Moroccan rap (a fusion of traditional Moroccan music and Western rap) and to find the adequate phrasing (a mix of Moroccan Arabic, called Darija, Amazigh (Berber), French, and English). From the end of the 1990s, the opening of the country played a crucial role in the expansion of musical genres of the new Moroccan scene, and numerous choreographers were interested in hip hop dancers and integrated them into their creations. The first Moroccan rap album came out in 1996, by the group Double (Aminoffice and Ahmad) in Salé under the label Adoua’ Al-Madina) and breakdance, dance phenomena of the street that began with rap culture. That phrase had meaning for me. My neighborhood in Salé in Morocco is a poor place constructed by “subordinates”, people excluded from society and victims of a system. They are the ones who built their houses in this neighborhood with their own hands. This place is linked in an indirect way to colonization, because the owners of these properties were more or less close collaborators of the powerful and the ministry of the interior at the time. They subsequently received the green light to sell these tracts of land without plans. They came taking these hectares that they didn’t even inherit, for their grandfathers had already taken these land. Then, when the French began to leave Morocco following Independence in 1956, these plots were bought by the people who currently live in my neighborhood, in the 1970s. These neighborhoods progressively became cities. The population built their houses without plans or authorizations—it’s become a real social problem—beyond Salé in Marrakesh, Tangiers, Casablanca, and the rest of Morocco.

When I wrote, Life is hard but we’ll resist, it was truly this idea of resistance but without having the tools of art. After, I worked with different images without having a knowledge of art. When I began to paint, it was after having met someone who encouraged me. In the beginning, I worked outside of art. In 2005, I was invited by a Russian artist and musician and by chance his father was a painter who taught painting at Moscow University. I stayed for a year, going between Moscow and St. Petersburg. It was the first time I left Morocco and I frequented “professional” artists, but it was also at this moment that I understood the notion of the city and public space. A year later, I returned to Morocco and transformed a garage in Salé, that opened onto the street, into a painting studio. Everyone in the neighborhood would stop in front of it: a person who just got out of prison, the neighborhood teacher…people met here to talk or to smoke a joint. After, several of them realized it was “easy” to paint and began to make abstract paintings. Some of them professionalized and sell their paintings today. This garage was a positive element, this thirst for communication was visible. In such neighborhoods, there is hardly anything; there is poverty but also illegal businesses.

KB : When did you begin to know contemporary artists in Morocco?

ML : I worked on my own, without worrying about what was going on around me. I participated in two editions of a workshop called Art, Technology, Ecology (2009-2011 at ESAV in Marrakech) organized by Abdellah Karroum. After Russia, it was a new experience in which I took part; with Antoni Muntadas, Younes Rahmoun, Mohamed Arejdal, Ivan Boccara, among others. Muntadas deployed a working method; at the time this interested me, as I didn’t know this language. There was a real mix in the people invited.

To come back to my work, I realize now that I made art before wanting to make art. When I discovered art as a diffused image—as well as a “colonial image”—I immediately made the connection to painting. I didn’t know anything about painting, except for the way in which I painted for a long time was abstract expressionism. I didn’t know all these American abstract painters and it was perhaps a form of therapy for me. Afterwards, I made works and interventions that allowed me to appropriate space. I painted heads of the minotaur at the time: I saw in the Marais in Paris a sculpture of the head of a bull in bronze, and I appropriated this form to link it to what I was doing in Salé. At a certain moment, it became clear in my mind that the studio was the city, and it was in this continuity that I began to make interventions with a sharper conscience of artistic and social issues. I thought that in art, like music, you can’t be an artist just like that to have status in society. Art is above all an interior need, after which it is tied to context, daily life in which you can do what you want with your art.

KB : To follow our discussion, I want us to talk about your current project, called Ex-Voto. When you first spoke to me about it, we were in Rabat. I remember very clearly because we walked from Place Pietri at the Rabat Ville train station and you had brought your daughter’s empty stroller with you, because it was blocking the stairwell in the building where we had been just before. I found this moment quite similar to a performance by David Hammons as well as loyal to your personality, with all the humor that was in the situation. A while later, I read the first presentation text that you wrote on the project; and I felt at once this feeling of bitterness (in the “thank you” of ex-voto that you turn on its head) but also a form of indifference. You try to install a form of ambiguity in relation to what we see, to this hidden message, to the history that is inferred. What was the trigger for the project?

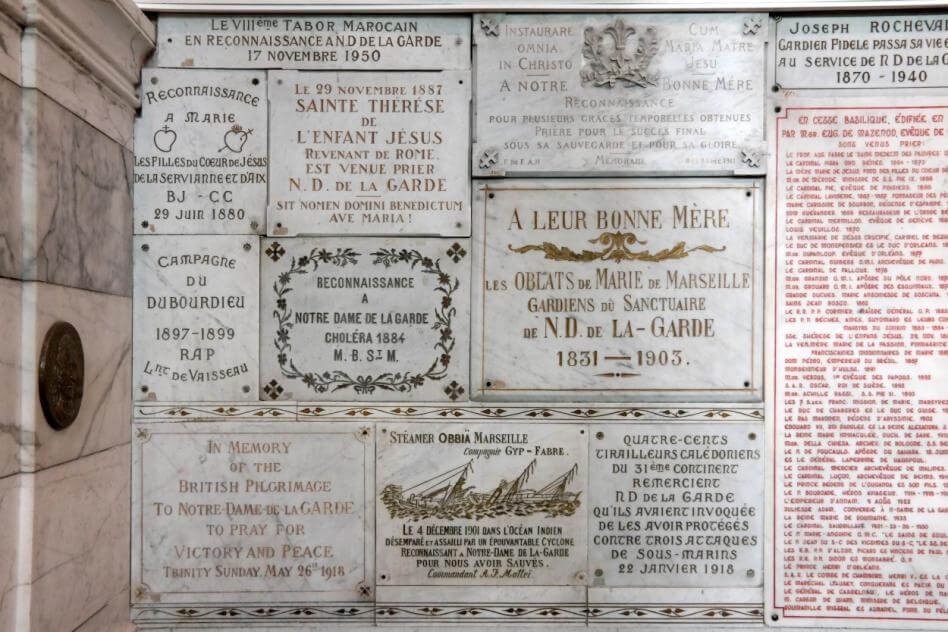

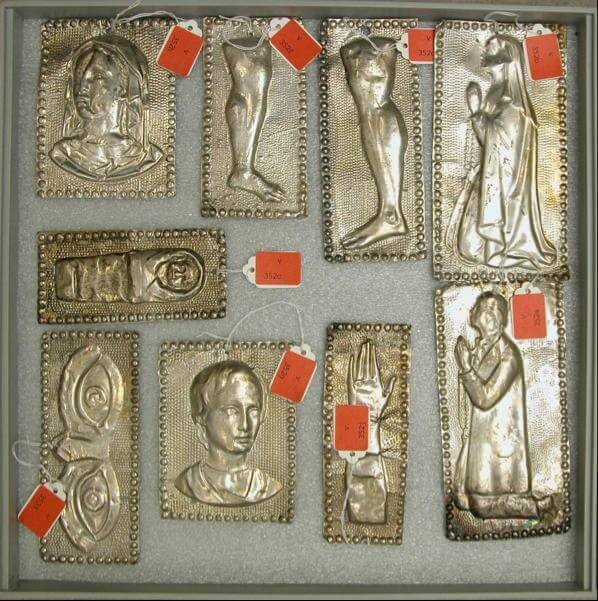

ML : This project is tied to my travels between Salé and Marseille. Salé is a town of immigrants, so almost half works in Italy, in Spain or in France. Ex-voto is doubly tied to these two cities. During a visit to the Basilica of Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde in Marseille, I discovered this sort of imposing and magnificent installation composed of marble plaques that we call ex-voto, and that also took the form of paintings representing boats, etc. This form interested me, and in seeing them, I immediately appropriated this space and these ex-votos that I wanted to hijack. Mentally, I imagined and conceived the first plaques in my mind. A part of these plaques are also found in the public space, meaning outside of the church where a large number of ex-votos are.

ML : In parallel in Salé, about twelve years before that, a guy I hung out with inherited a Renault 12 from his father who passed away, a retiree of the Renault company in France. His son, Salah, inherited this run-down car that wasn’t even worth 500 euros. While he was inheriting it, he secretly went to Paris; that’s where he is now. Salah left and so this R12 was left in my garage. This car stayed in the garage during the five years I was there, a Moroccan who lived in Paris lent it to me in exchange for paintings and he turned out to be Salah’s cousin. During this time, the inheritor of the car suffered the same fate as the R12 but in Paris. Thus, I saw this church in Marseille and in parallel this image and history of the Renault 12. The discovery of this Marseille public space set off this whole Renault story and the migrations around it. So, I conceived my first ex-voto “Merci Renault” in the form of an engraved marble plaque, but I also used the relic of the car (Salah’s inheritance) - shown in the public space as an ex-voto - and tagged “Merci” on it.

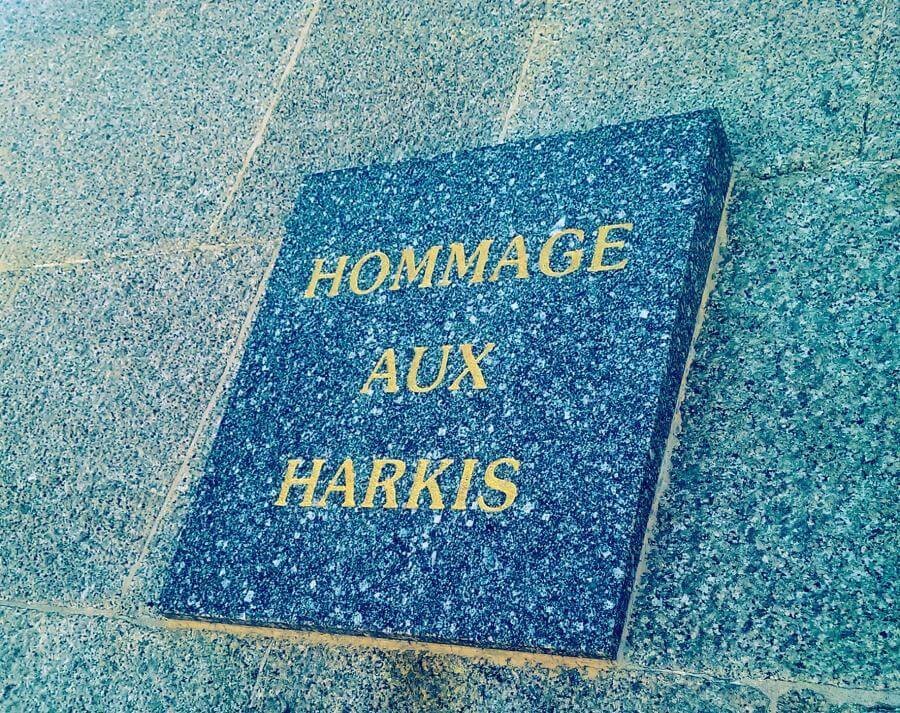

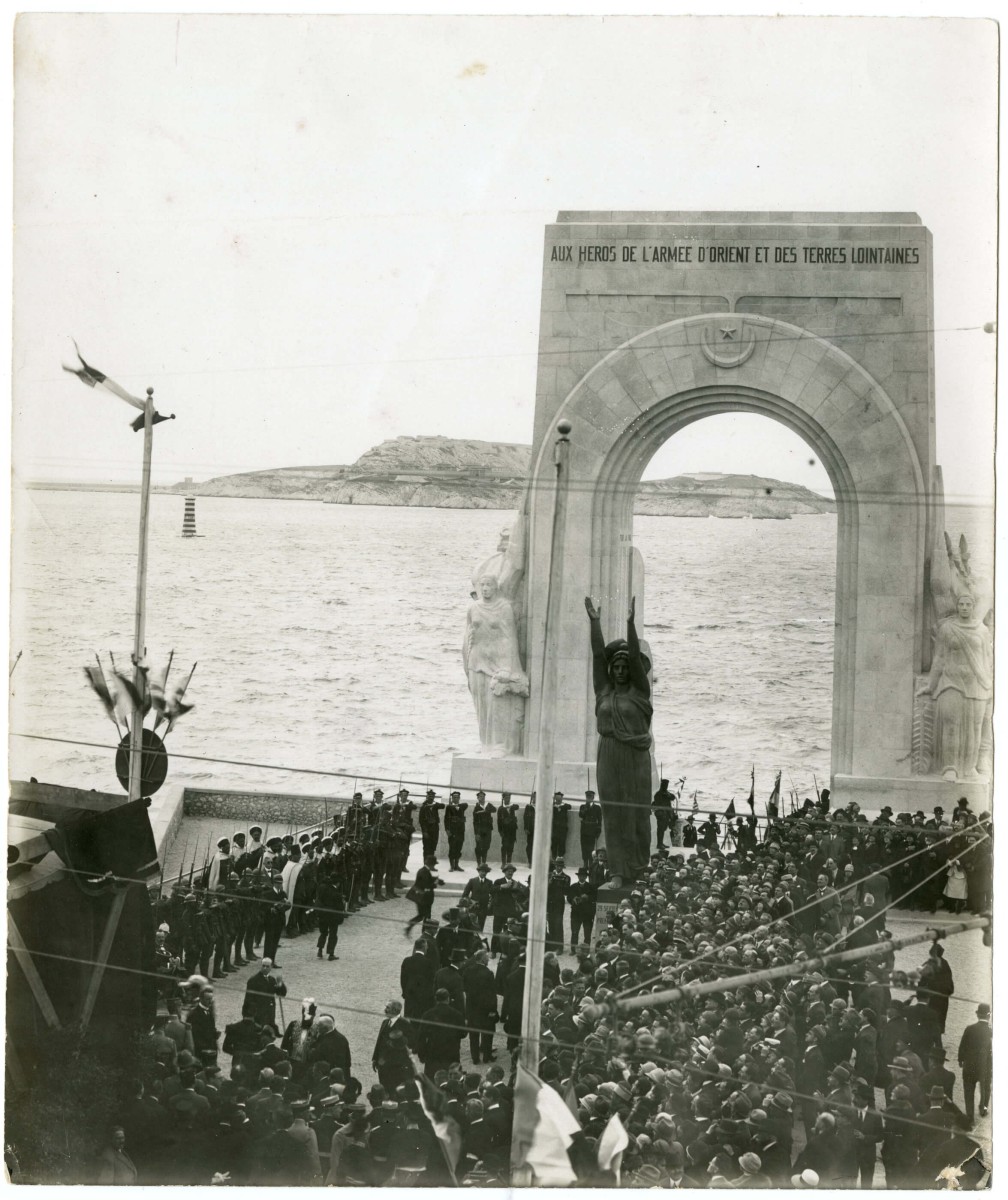

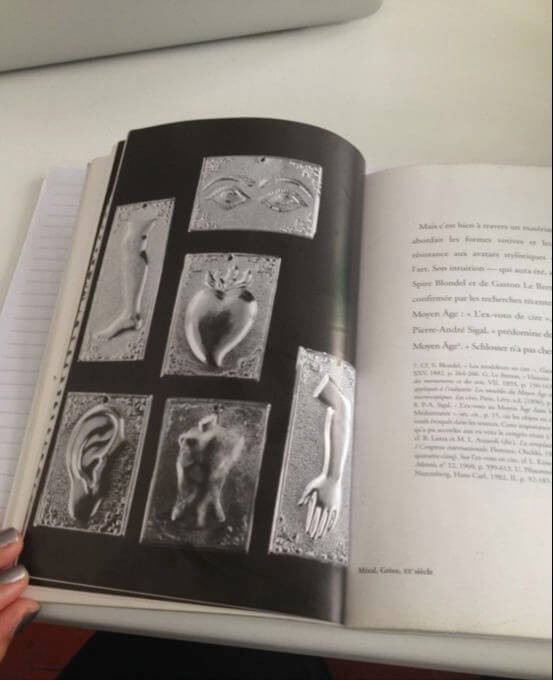

ML : During my flâneries in the city, I visited a monument close to my place in Marseille, on the Corniche. It’s a monument to the deaths in the Orient and far-off lands (A monument dedicated to deaths in the Oriental Army and far-off lands during the First World War. The French Army of the Orient (AFO) is a unit of the French army that fought during WWI on the Oriental front between 1915 and 198. Called the “Door of the Orient”, the monument consists of an arch turned towards the Mediterranean Sea and is situated on the Corniche in marseille., an homage to the Oriental Army). In the manner of ex-votos, this space also as a function as an homage, there is a similar aesthetic between the two. There are several plaques on this monument, including one in the back that pays tribute to harkis. As soon as I saw it, I immediately made a frottage with pencil of this plaque on a piece paper, giving the Ex-voto project different forms. In general, we find the ex-votos in a multitude of forms, in clay, wax, plaques, sculpture. You should read Georges Didi-Huberman’s Ex-voto.

KB : In art history, there is a multitude of ex-votos, sometimes painted, sometimes in the form of marble plaques. I have the impression that your project allowed you to tie Marseille and Salé together, but also a history of work and immigrants between these two continents. The Renault becomes a symbol of France, but it could have also been bought because there is the cheap manual labor done in France by Moroccans.

ML : With this intervention with the car, I’m focusing on this object now: it’s visible in Salé and “exhibited”, confronting all the people in the neighborhood. All this has meaning in relationship to the action that I did on this car. The “every man” of the neighborhood will see this “Thank you” tagged on the car, and will ask “Why thank you?” This situation interests me. Through my art, I played golf in a run-down terrain (Golf Project, 2012), I put wings on a horse in a vague terrain of my neighborhood (Everything is sacred, 2013), I fed the magazine The Economist to a homeless beggar who is also the victim of the Moroccan economic system (L’Econome, 2012). All this, put into perspective with the gesture of tagging “Thank you” on this car makes things more explicit. It’s a way of playing with a form of indifference that you mentioned before. There is also humor in all of this, we don’t know if we should laugh or cry. These neighborhoods are for me the wound of a city like Salé. The causes of the situation of these spaces come from given political circumstances; there are of course people who are behind it. Forty years later, people die in barges after wanting to immigrate to Europe, others are now immigrated and are slowly being extinguished in France like Salah. In regards to the architectural and spatial plan, the Renault is truly an ex-voto suspended in space.

KB : It’s also the beauty of street art and these kinds of interventions like yours, when we wander through urban space, we receive a multitude of information. For example, an inhabitant of your neighborhood in Salé who leaves to work on the other side in Rabat at six in the morning will pass by and see the Renault tagged with “thank you” and wonder why.

ML : The second part of the project Ex-voto is made up of all of the documentation tied to colonial history: images of colonial exhibitions, historic information that from the French and Moroccan sides deal with protectorate. I wanted to repaint these images in collaboration with a street painter.

KB : Is that a reference to a particular tradition?

ML : Yes, in Mexico for example the street painter paints ex-voto. What I treat in this project is not innocent, it is intimately tied to Catholicism, itself with strong ties to colonial history. I found a man in the Old Port who draws very well, he’s maybe going to make drawings for me, and I also found another person in Rabat.

KB : Is it easy to find people who draw and paint in the street in Rabat?

ML : There’s a particular place in Rabat where the city gave studios to street painters. I could also maybe ask a woman street painter to paint my ex-votos. The place of women in colonial history is also interesting to put into perspective today. The first part of my project unfolds with ex-votos in the forms of plaques and actions, like with the first action of the Renault 12 in Salé, and the second with the frottage of the ex-voto in memory of harkis that I mention earlier. Or also how a simple tag can become a photograph and the way in which an ex-voto in marble becomes a drawing. The next step is more about its collaborative aspect with the participation of the street painter. In the marble ex-votos, there are references to people like Leopold II (Leopold II (1835-1909) became the king of Belgium in 1865. He created the Congo Free State after the Berlin Conference in 1885. (1835-1909), Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898), Renault, etc). For example, the history behind this plaque that you see here is incredible (Taverna del Re, acknowledgements), about four months ago, five millions tons of trash were brought from Italy from the Taverna del Re in Naples, and were thrown away in Morocco in order to be burnt. Veolia is a company in charge of garbage in Morocco (Merci Veolia). There is also the Duke of Tetouan Leopoldo O’Donnell and Joris who is from a Catholic background. He was the head of troops during the invasion of Morocco when Spain conquered the north of Morocco. This plaque makes reference to this historical personality, placed side by side with other plaques with the mention “Gracias”, and works very well also. I make a reference to the German chemist Hugo Gustav Adolf Stoltzenberg who invented mustard gas, a chemical weapon used against Abd El Krim (Mohammed ben Abdelkrim El Khattabi (1882 in Morocco - 1963 in Cairo), frequently called Abd El Krim, is a Moroccan resistant from Rif. He became the head of a resistance movement against France and Spain in Morocco, during the Rif War, then an icon of independent movements against colonialism.) during the Rif War (1921-1926). The ex-votos allowed me to create a story, to play with the visual field, the information, and histories that are found inscribed on all of them.

KB : You also use several languages in your ex-votos, and this reflects the reality of Morocco, its history, and its geography. I find incredible the plaque with the inscription that mentioned the presence of 750 French companies in Morocco…

ML : In Morocco, there is an old tradition of artisans working and sculpting motifs in copper, which make trays, etc. This reminds me of this image in the book Ex-voto: Images, organ, time by Georges Didi-Huberman. He speaks at one moment of wax in a historical manner as as a material used for ex-votos. He explains that wax is a truly living material that allows certain things that other materials do not. For example, if someone limps, and made a wax leg as an ex-voto, as soon as the person was healed they had the possibility of melting down the wax in order to re-use it. The wax ex-votos I’ll make in Morocco, once shown, will then be melted to make others in Algeria, as Morocco as a particularly relationship to Algeria.

This idea of melting down a material to make something else appeals to me.

KB : Here in the book, Didi-Huberman writes “(…) Wax appears and disappears, it can constantly reappear in new organic fixations, it is polyvalent, reproducible (…) exactly like the symptoms that it attempts to represent in a way, endure in an other way.” In reading this passage, we can see the correspondences with your project in which ideas and forms circulate and manifest liberally.

The artist:

Pinning down Mohammed Laouli (born in 1972 in Rabat), an artist who splits his time between Marseille and Salé, Morocco, is not an easy task. Among his works, guided by different dichotomies—history and social organization, thought and action—of particular note are performances, photographs, and videos. During a recent visit to Marseille, I went to his studio where we discussed his subversive approach to History and the paradigms of our era. The questions he seeks to generate on the role of creation, our position as individuals and citizens are broached implicitly in this interview, particularly with his most recent project, Ex-voto.