Nothing Human is Alien to Me

In early September 1981, Ingmar Bergman invited a hired cast of actors to lunch in order to have them meet prior to the filming of Fanny and Alexander (1982). While there is nothing unusual about a director wanting to bring together his forces before battle, Bergman thought it novel and curious to film this meeting. Whether he had a peculiar agenda for filming this meeting or not, a miscellaneous record was caught on film, and the director rolled the camera on this moment. From the outset we see everyone at ease — fresh and gleaming — with the expectation of the enterprise lying ahead. Dressed in typical Scandinavian fashion, full of bright but washed pastels, the actors relax cozying up to one another. Every time the camera of this pre-production document gazes straight into an actor, silent smiles emerge along with the civil intimacy of colleagues. In short, we see a ready-made community forever integrated on celluloid and bent optimistically on the near future to come.

We can argue that while actors are more or less familiar with one another in the field, the sensation you gather from looking at the film is one of heightened social excitement, similar to those rendered in Renoir’s impressions. The thirty years between now and the making of this document attest to the biological and social time that has passed, and while things might seem “dated,” the promising (and simultaneously, the retrospective) success of Fanny and Alexander ignites this first meeting. Not only as an example of life but as confirmation of an accounted future that materialized. So tempting it is to have material of this kind that Ingmar Bergman eventually includes this footage to preface his behind-the-scenes film Dokument Fanny och Alexander – The Making of “Fanny and Alexander” (1986). The inter-title statement introducing the documentary points our way: “The day before shooting started, we met to say hello, to show ourselves at our friendliest, and perhaps even to conjure up a certain excitement”. And as such, we have life not just behind the curtain of cinematic appearance and spectacle, but the documentation of life before artifice as well.

“Nostalgia. It’s delicate … but potent. Teddy told me that in Greek, nostalgia literally means the pain from an old wound. It’s a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone. This device isn’t a spaceship. It’s a time machine. It goes backwards, forwards. It takes us to a place where we ache to go again. It’s not called the Wheel. It’s called the Carousel.”

Mad Men, Season One, Episode 13, “The Wheel”, 2007 © Lions Gate Television, Inc.

As a film curiosity, the capture of a meeting of actors-in-leisure evidences more than the diplomacy of the workplace. It stands rather remarkably as a declaration of community. Hinting to an elegant utopia, even if a temporary one, as we know that film productions are structured by short-term budgets, industry specialist, and professional talent. A miscellaneous film of this kind is but a looking glass curiosity of conviviality before commodity, of gregariousness before mediation. You might say one has had the privilege to experience the promising ensemble before it is submitted to aesthetic rendering.

In uncovering these moments, either recorded, filmed, compressed, and digitized we find that something has been preserved beyond the notion of encapsulated time. Life was enacted but simultaneously sustained, lived in the full sense of the word but consequently framed and, thereby, postulated for posterity without ceremony. It holds true that we do not get from such a slice the individual psychologies or the intellectual variables of social interaction from each actor. This is the realm of memory and, further, the delving into the politics of the production itself. Instead we are given a condensed space and time snapshot of the well-being of this community in the making.

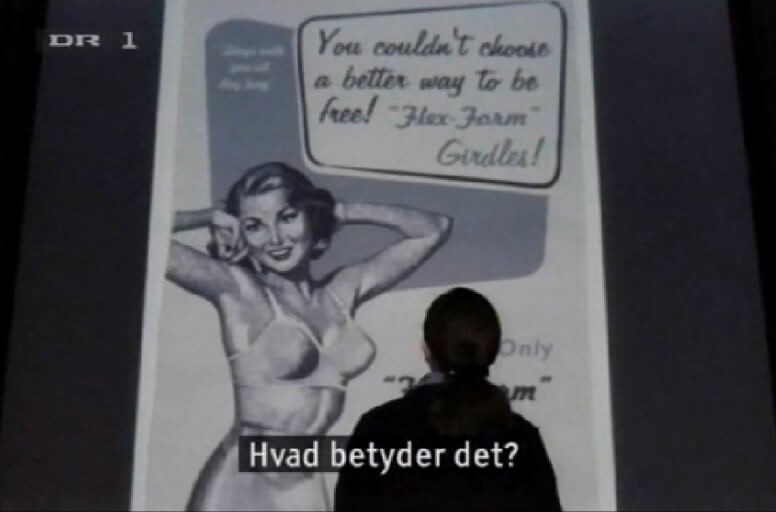

In recent years fiction has tried to relate back to audiences the triumph of advertising over social behavior psychology. It is of course an established discourse the idea of “life captured” as a convention of commercial media. One can see this gloriously constructed in the episode called The Wheel of the television series Mad Men (2007), where the protagonist of the series Donald Draper shines his genius over the marketing of Kodak’s Carousel Projector to a boardroom full of executives. His “pitch” outlines a retrospective journey between nostalgia and the capturing of life as desire, building expectation through the display of memories shifted with each slide and his narrating voice, creating emotion over the ownership of a Kodak slide film projector. You might as well call it an anti-Godardian product placement, hitting strikingly close at the heart of the relationship between film, narration, and memory. Curiously enough and with a deep sense of anachronistic irony, Kodak over the last decade got rid of these film-dependent products as digital wares overpowered the analog market, which eventually hurled the company into bankruptcy.

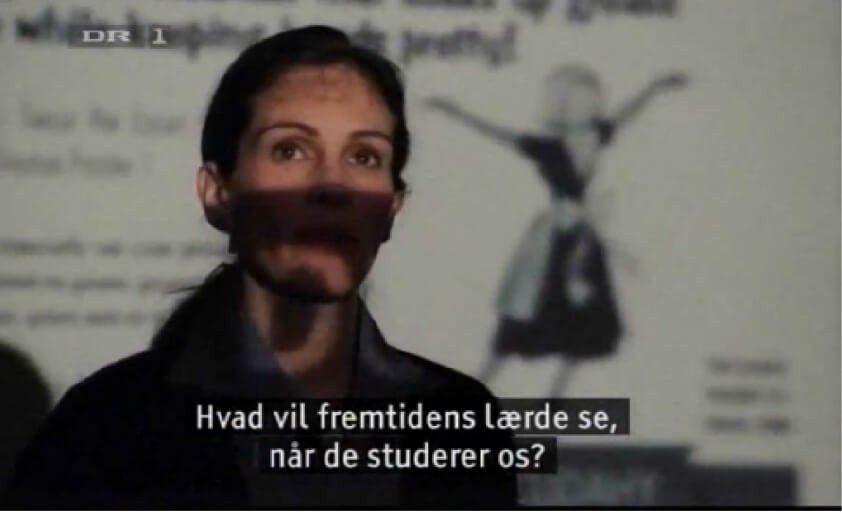

Just as curiously, visual culture academics often wrestle shadow puppets of influence with image production agencies over the subtleties of images introduced in the public realm on one hand, and cold, hard cash on the other. The dialectic tension between the two is of mutual importance, simply because, in a capitalist economy one is forming the other. It is rather amusing, to think that the highest ever paid university lecture did not happen in “real” life but in fiction, in the film Mona Lisa Smile (2003). Julia Roberts plays the part of a university art history professor who challenges conservative Wellesley College girls with proto-visual culture lectures, all of them tinged with feminist analysis of the gendered and socio-political status of women in mid-century America. However, even as the college’s tradition building rhetoric tries to pull a mantle over our heroine, we see her character and the actor triumphantly check out with a reported payment of 25 million dollars, often suggested as one the highest-ever paid fees for an actress in Hollywood history.

“What would the future scholar see when they study us - if we as a people just had that in our mind the world would be much more different and a much more good place to live in…”

Mona Lisa Smile, 2003 © Sony Pictures.

While the temptations of fixing critique upon the ideological meters of producers are necessary (especially to separate us from sheer propaganda, art, or a mix of both) our interest in this essay lies elsewhere. It is given in the history of things that being human precedes the simulation of human experience, and then it is rendered in art. Situated as archival or supporting material, the “behind-the-scenes” “making-of” and “bonus material” captures (outside of the commentary or voices from participating actors and producers) life somewhere between human drive, memory, and the imagination promoting to produce the art. While purely in the domain of “documentation” these variants available possess a parallel existence outside of the notion of documentation and memorabilia. They are live motion vestiges of our psychology, behavior, context, and sustainability that in fact activate, rather than just evidence, our human need to create.

La Sortie des Usines Lumière à Lyon – Workers Leaving The Lumière Factory in Lyon, was filmed by Louis Lumière using his Cinématographe, a device that can shoot, develop and project film.

Life as it is conserved in miscellanea — even if artists produce it — is an animated record of our existence without the confines of ideology. Without exaggeration, these exhibit more or less precursors of creative freedom, when they end in capturing the actions of creative communities through their dwelling, their intimacy, their social behavior, and most importantly through their labor. Miscellanea are more or less salvos expressed through time in continuity with the phenomena caught in early film history through films such as La sortie des usines Lumière à Lyon – Workers Leaving the Factory, L’arroseur arrosé – The Sprinkler Sprinkled, and Repas de bébé – Baby’s Meal (1895). All are variables of human dignity in motion, where the fullest sense of “play” is given and no celebration of it has to be instituted or mediated, since it “just is”. Even in its shades of gray, before the regime of enterprising aesthetic manipulation begins, what is captured is being conserved and to our surprise — making demos of our cultural stars. The converse of the previous paragraph could be read as life before ideological representation rather than ideology before life as representation.

L’Arroseur Arrosé –The Sprinkler Sprinkled is considered by many as the world’s first comedy and was shot in Lyon in the spring of 1895.

The film stars Andrée Lumière (baby), Marguerite Lumière, (wife) and Auguste Lumière (husband)1895.

All three films above were shown 1895 at the Grand Café on the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris.

What is suggested is that in these miscellanea, supporting materials, snippets, out-takes, bloopers or the “making of” is that an aspect of human experience outside of artifice and art has quietly been resisting a comprehensive history or for that matter an art form. A potential to find creative, political or social acts in these human actions recorded on film has yet to be uncovered.

So how can a few gatherings of people, pleasures or struggles in the service of a completion or battle to accomplish a movie, exhibition, invention or a project help us measure the distance between we the living and those having lived in the space of miscellanea?

How can we see these as candidates for conservation, not only justified in the “archival fever” of the last decade, but acting dynamically as part of a greater question concerning the conservation of our past selves as an end in itself? After all what are the criteria for what is being conserved? And finally, what of what is being conserved has the potential to emerge beyond art itself?

We have to turn to the future for a second, and imagine that the velocity by which we are transforming is changing what we consider human by example. There is a major transformation of us as humans on the way or as we proceed into the murky future. While plenty of studies have demonstrated that our parents’ bodies in the Sixties were radically different to ours today. Or further, for example, that the descendants of American civil war soldiers are physically taller, fatter, and as well cannot fit the tailored uniforms of their great-great-grand-fathers today. We have in fact changed.

Things are changing invariably as we see in these documents that we might not exactly be like the people we visually consume in visual material from thirty, sixty, or ninety years ago. In other words, we have crossed under a gross aesthetic and material climate change and it is perhaps this transition that gives us agency to look for material, which may serves us — beyond memory — as paradigmatic background to the transformation of ourselves as climate change continues. Perhaps as a way to bring us back to ourselves by seeking gauges of what atmospheric typology we desire for humankind. We can keep in mind that on one hand, we have the servile and conventional nature of these bonus documents, but on the other these incidentals are life beyond art itself. Something has emerged in these conservations of being, which as we have observed are lives lived before an aesthetic vessel has been assumed, while in regard to our future selves they reference sources of well-being against the crises and deterioration we will experience in this future.

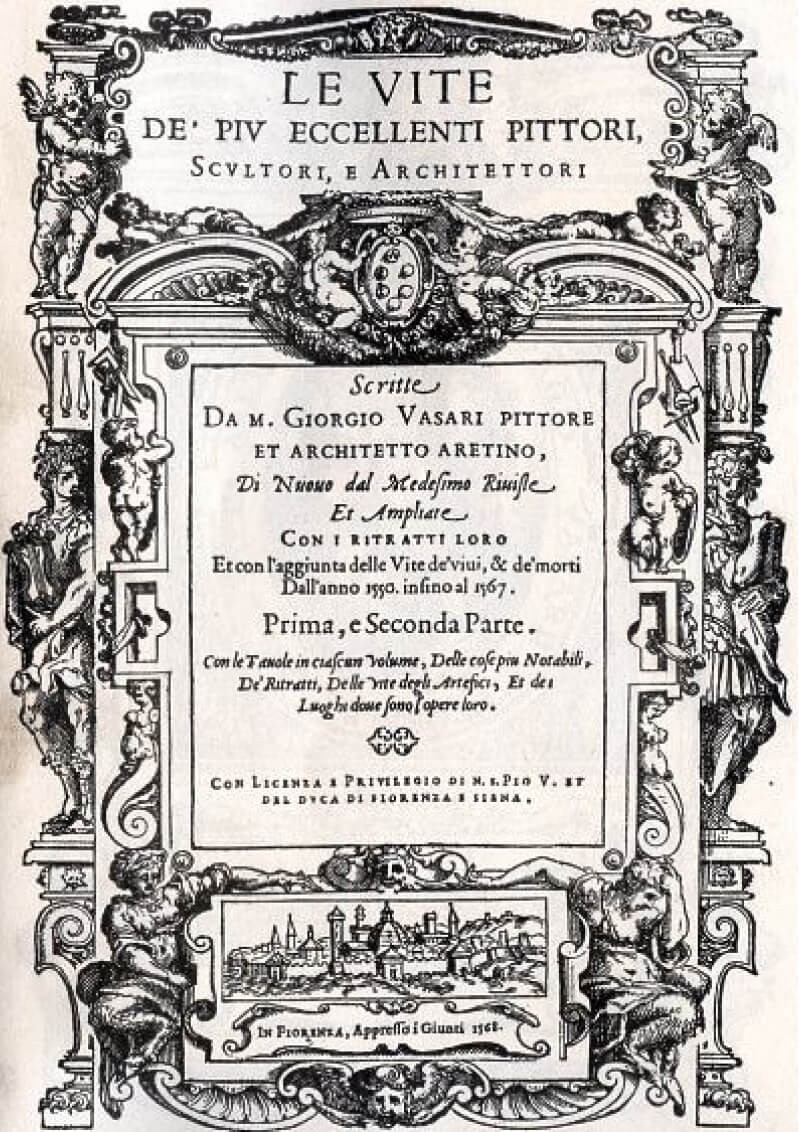

Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri – The Lives of the Artists, 1550 (enlarged 1568). Image is from the tiltle page of the 1568 edition.

Moreover, without a question these miscellanea are unstructured continuations of Vasari’s format that he established in The Lives of the Artists (1550, 1568) and which have been migrating quietly through time taking on new variants of content through each century. However biography may be flirted upon in the anthologizing of lives. Our miscellanea trump biography in that it animates bios figuratively over dimensions of life and action that text driven biography cannot capture. It does not matter if vanity, narcissism, or shear megalomania has produced these documentary impulses. Life as a subject has been animated, instead of “lives” as objects graphed. Making the process of capturing aspects of creativity in-progress an end in itself. Quite simply, the subject is predicated upon the inclusion of all peripheral renderings related to creativity, no matter how tedious or brilliant or poetic they may be – they encompass a potential history of creativity outside of the art object and which is not yet understood.

Miscellanea correctly belong to a category of representation, which may comfortably rest in archives, but as well be above them, pointing the way as future content for a comprehensive reference system that could be concerned with the conservation of human behavior, enterprise, and dwelling as knowledge – (perhaps as an encyclopedia of being?) one playing a part in the launching of a pre-aesthetic epistemology that could potentially ignite a political imagination, which could be serving the establishing of sustainable standard in the otherwise statistically calculated and deteriorated future to come.

Simply with the potential to delve into asking, what is to be Human? Our media based salvos are just that — an approach among many to the complex salvation we aim to find. It is evident that the world is in denial. The persistence of negative climate change eventually will push humanity into a radical answer regarding the transformation of our planet away from deterioration.

This means that our relative values will have to cede somehow to new social, biological, and economic values in order to make this planet a livable one. It begs the question, how can we reorient our politics, our affairs in order to repair entire sections of our world? Should we not start with redefining our notion of being Human? Perhaps rethinking the aesthetic intervals of what makes sustainability a comprehensive aspect of the environments that we want to live in? We want to sense in? This means that creative-political imaginations have to emerge that will deal directly with the aesthetic dimension in order to enable the sustainable and resilient world they imagine, keeping in mind that the intent for setting up such aesthetic will require reproduction and absorption implementing ethics and politics that are expressive in this bridging aesthetic. The potential to activate a radical sustainability, which in essence has a healing reconciliation in mind, has to come by calculating what we see against what we have lost. This in the end has very much to do with visual terms – that is ‘what you see is what you get’.

All this has to do with setting up a comprehensive aesthetic reorganization of life, closer to Bruce Mau’s Life Style declarations of a decade ago than to Al Gore’s admonishments. How we rethink what is sustainable in the physical world and how we manage the politics to realize the space for repair, healing, and restoration is going to be the defining ethos of this unfolding century. Quite potentially we have to consider that our past will play a big role in the organization of this aesthetic in the future. Here it might just be that retrospectives will be the hind-sighted events and politics of this restoration project. This means that “looking-back” industries could be imagined and implemented in all areas of culture and society once the secret of our actual demise is out. How they will walk the line between social conservatism and progress will also have to be considered. How we politicize retrospectives in the coming future; will be the yardstick of our success and failure.

And as such, miscellaneous musings are part of a subtle pedagogy of hindsight, the core aspect that enables retrospective imagination, production and representation. They are helpful in the sense that they can help us imagine how to model sustainable life as we look back. They have the potential to give us the necessary leeway in establishing contrast and agency between what we imagine as well-being and what we know how to implement as well-being. Finally, in essence they suggest being part of a poetic fragment of the whole search for aesthetic mitigation – especially in our creative struggle as eventual people facing an uncertain future.

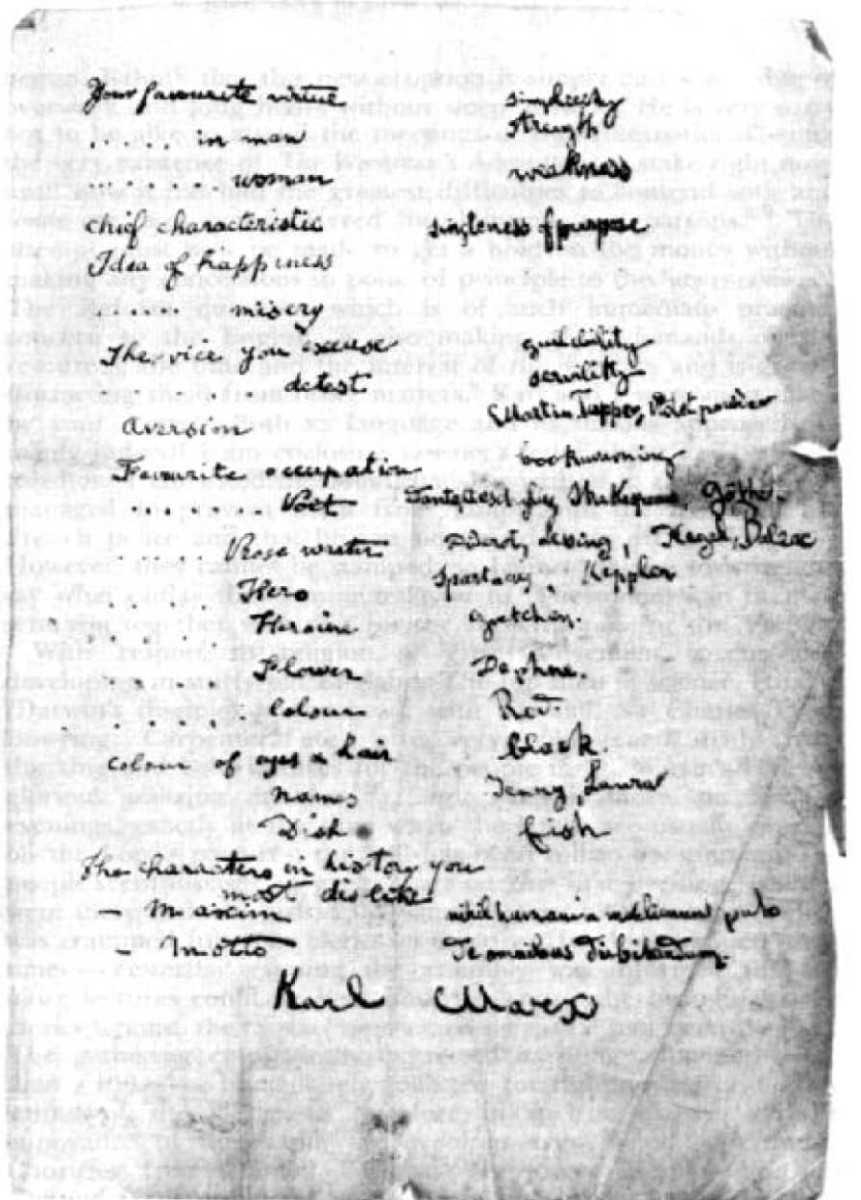

The title of this essay is taken from Karl Marx’s favorite maxim declared while playing the Victorian parlor game Confessions with his daughters and his uncle Lion Philips in 1865. His daughter Laura Marx penned all the answers in an album kept by her sister Jenny Marx. A number of versions of Confessions belonging to Marx have been spared. The game is known today as Proust Questionnaire.