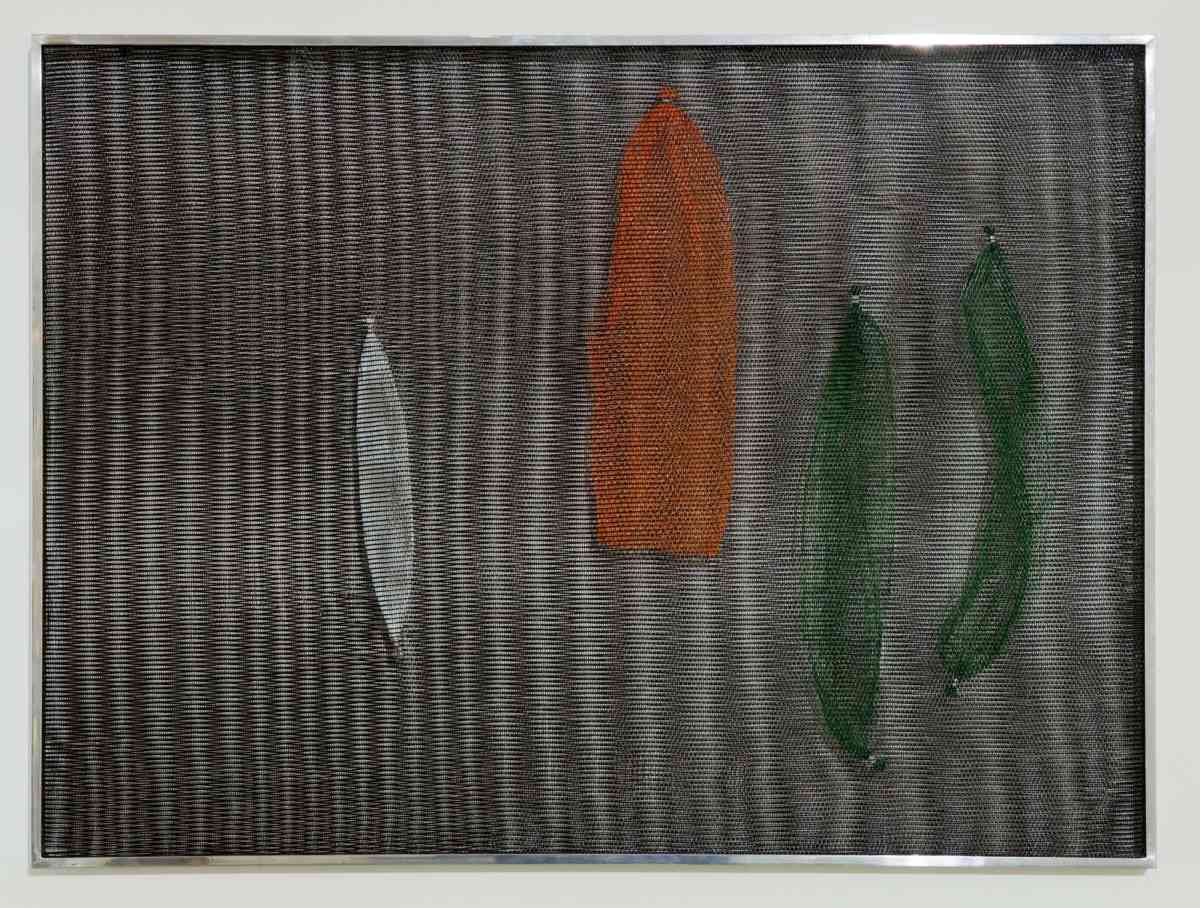

Les formes féminines

Exhibition with Eva Berendes, Monica Bonvicini, Kristina Braein, Delphine Coindet, Julie Dawid, Tatiana Echeverri Fernandez, Jenny Holzer, Séverine Hubard, Claire-Jeanne Jezequel, Colombe Marcasiano, Falke Pisano, Lili Reynaud-Dewar, Jessica Stockholder, Jennifer Tee, Lina Viste-Gronli, and Julie Voyce

April, 4 - May 23, 2009, public opening on April 4, 2009 from 6PM

Galerie de la Friche Belle de Mai, La Tour, 2nd floor, 41 rue Jobin, 13003 Marseille

At the origin of this exhibition lies the idea of a rough and curious parallel between the history of sculpture and that of women in the 20th century. Modernist goals, universality; the forced yet accepted submission to codes and conventions: sculpture realizes the dynamic tension between tradition and modernity. It embodies unity, a simplicity of interpretation. At the same time, its deviations are not easily forgiven: contemporary sculpture quickly becomes parodic. Sculpture “embraces” its gender, and it is inherently performative (1). A sculpture that asserts itself as such is one that holds something symbolic related to the status of sculpture (which painting can do, but video or installation struggles with, risking quickly slipping into caricature). Sculpture claims, in a certain way, even if ironically (2), its status as “high art,” even if made from poor materials and waste. Belonging to the genre means being able to claim a standpoint. Knowing that this standpoint is not omniscient is a good start to appreciating the accuracy of one’s own observations (3). Like the biological and physical sciences, the field of art can be re-invested post facto through the lens of gender theories. Some things remain forever lost (4), but others, once abandoned, can be reclaimed and improved. Historically, women artists struggled to implement modernist theories for circumstantial reasons (and not intellectual or related to any “feminine” nature), notably because of the art world’s “intermediaries” (gallerists, curators, critics, historians), who were predominantly male and delivered reductive symbolic interpretations based on the gender of the artists. A century later, it is clear that the viewpoint has shifted, and it is increasingly difficult to formally qualify productions as “feminine,” even though such assumptions still persist in everyday language. Paradoxically, it seems important to emphasize the historical emergence of a feminine perspective in the 20th century (alongside black, gay, and general community viewpoints) because, ironically, it is this emergence that allows feminine practices to be finally seen as neutral. The age-old struggle between the artist’s subjectivity and the supposed universality of aesthetic language seems to intensify even more when, in addition to being an artist, one is… a woman.

It is therefore interesting, at the beginning of the 21st century, to remain silent for a moment and experience aesthetically works that claim nothing less than to be clearly derived from the modernist tradition (thus objectivity) while being created by women artists (thus standpoint). The exhibition, beyond its political aporia, offers a unique landscape where abstraction dominates and where criteria dissolve, making way for a “queer,” “strongly objective” sensuality. Sometimes, states of crisis are not meant to be overcome: according to sociologist Elsa Dorlin (5), “crisis is also an opportunity for the production of heterodox, contestatory knowledge that undermines and challenges dominant theories.” Any resemblance to an existing situation might, for once, not be coincidental.

(1) I am explicitly referring to the theories of Judith Butler developed in Gender Trouble

(2) See Susan Rubin Suleiman’s essay on the figure of the “ironist,” Epilogue: The Politics of Postmodernism after the Wall: or, what do We do When the « Ethnic Cleansing » starts?

(3) See philosopher Susan Harding’s concept of “strong objectivity”

(4) I think of Lee Krasner…

(5) In Sexe, genre et sexualités?, Philosophie Collection, PUF