Hélène Rivière

Hélène Rivière is an Astérides Resident in 2010. The archives of Triangle-Astérides do not allow for the determination of the exact dates or the duration of this residency in 2010.

“The Radiance and the Mystery”

Pastel

Hélène Rivière, a young artist trained at the ENSBA and the ENSA in Toulouse, has for several years been producing pastel drawings in various formats which, thanks to a recent residency at Astérides (Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille), have gained scale and begun to occupy space. The series Modules (2010), a perhaps provisional title, includes panels, tubes, and tondi covered in paper drawn on with pastel, gathering works whose dimensions can exceed two meters. The exhibition thus presented a deployment of “pastel” color in space, through soft, abstract forms, bursts of light, and tremors of varied tones, evoking both the world seen through a microscope and those luminous spots that seem projected onto our eyelids when we close our eyes. One might be reminded of Cécile Bart’s work, with this spatial architecture built through color—but to stop there would be to overlook the broader scope of Hélène Rivière’s practice.

Indeed, Hélène Rivière has a particular command of dry pastel drawing, which enables these subtle blends and colorations that are at once vivid and soft. Though she has also used other techniques—graphite pencil, felt pen, colored pencils, ink—pastel now dominates her practice, and it is on this point that I’d like to first linger. Pastel is rarely used in contemporary art—even though drawing itself continues to be held in high regard. Pastel remains a technique that is both historically situated, bound to specific genres, and gendered within the traditional history of art. Invented in the early Renaissance, pastel became especially important in the 17th and 18th centuries; it allows for a rendering that is both truthful and sensual, making it particularly useful for portraitists: Le Brun, then Chardin, and especially Quentin de La Tour all made extensive use of it.

Thus, it became associated with an older pictorial genre—the portrait—and artists competed in virtuosity to render the blush of a cheek, the glint on a silver curl, the delicacy of lace, the fragile beauty of our world. What’s more, pastel requires a certain quickness of execution, and lends itself to an aesthetic of the non finito, even a taste for a certain delicate blur, which oil painting cannot offer. As demonstrated by the 2008 exhibition The Mystery and the Radiance at the Musée d’Orsay, the 19th century saw a flourishing of pastels—sought out to capture the mysterious glow of light on bodies, faces, and landscapes in the works of Degas, the Impressionists, or Redon. Thus, pastel became tied to portraiture and landscape, to genre painting—and ultimately, by the 19th and 20th centuries, to a particular gendered social norm: young girls from good families were expected to practice pastel with tasteful refinement, producing scrapbook-style albums mixing views and family portraits.

Nothing of the sort in Hélène Rivière’s work, which carefully diverts and subverts the history of pastel and its conventional associations. The abstract and fluid forms in the Modules series, for instance, break away from those genres, and their large formats allow them instead to deflect the customary interpretations often linked to pastel. The strange worlds these forms unfold from one “module” to another reflect a highly specific and precise work on color—both vivid and diffuse, radiant and absorbed—within the dry and delicate medium of pastel. This is a topological investigation of the technique, but one that belongs to the realm of abstraction, spatial expansion, and thus lies far from the intimate domain of genre drawing, portraiture, or landscape.

The work Transitions (pastel and graphite on paper, 355x150 cm, 2010), simply placed on the floor and resembling something like a staircase or a colorful hopscotch game leading us on a journey through color, appears as a sort of poetic art. Its steps, which form a kind of color chart, produce a surprising harmony of marbled hues. This piece shows how the artist’s use of this technique engages in a formal exploration that combines the fluidity of colored stains and the hardness of stone, the delicacy of material and the illusion of depth, architecture, spatiality, and drawing.

And when Hélène Rivière does make references to the traditional genres of pastel, these are delicately overturned. One series, Non Pays (thirteen drawings, pastel and charcoal on paper, 24x32 cm, 2010), deals ironically with the pastoral. Similarly, Banquets I and II (2010)—sheets of paper placed on a platform that, as the artist puts it, “happened to be there”—an uncertain space in depth, strewn with colorful cups, do indeed evoke a meal, but it’s more likely a philosophical or ancient Greek banquet, judging by the shapes of the cups, than a bourgeois genre scene of a family meal. Hélène Rivière thus demonstrates the power of pastel to transport us elsewhere, despite its historical associations with the here and now.

Paper Spaces

At this point, we must return to slightly older series that bear witness to both a search for elsewhere and a paradoxical use of pastel—often in combination with other techniques. I’d like to focus here on what might be seen as visual collages and the construction of spaces that can, in some aspects, evoke a theatrical universe for the viewer.

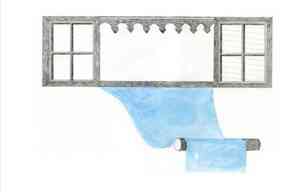

Indeed, Hélène Rivière also produces drawings that we might call, for simplicity’s sake, “figurative”—composed of representations of objects from the world within the space of the page: curtains, doors, windows, tools, roofs, partitions, trunks-columns. These elements, it seems to me, most often belong to the world of architecture, but in a subtle way. One thinks more of the elements of a “house,” of objects that allow for protection, covering, separation, and also connection between separate spaces (window, door). Some titles explicitly reference this world: Protection bancale (2009), Interstices à l’aide (graphite and colored pencils on paper, 58x42 cm, 2009), Chambre personnelle (graphite and colored pencils on paper, 24x32 cm, 2009), Windows (graphite and pastel on paper, 58x42 cm, 2009), Hutte isolée (graphite and colored pencils on paper, 42x30 cm, 2008), Cellula (graphite and color on paper, 21x30 cm, 2008). This list speaks volumes.

As we look through these drawings from 2008 to 2009, we observe an increasingly strange assembly of the elements making up the “cell”-room-house, which, by playing with perspective and the viewer’s desire to reconstruct a coherent space, creates scenes that are visually elusive, bordering on the absurd: a curtain floats along the bottom edge of a window; steps hang in mid-air leading to a door seemingly tethered to a shifting wall by threads; curtains and partitions intersect at impossible angles, threatening to collapse; a birdhouse roof balances on a small trunk—protecting nothing. The comforting, down-to-earth world of traditional pastel veers off course.

These constructions—entirely drawn, with a crispness rarely associated with pastel, in pastel hues uncommon in such surreal environments, though often structured by graphite—evoke collages. Elements are assembled, glued together, with no real reason to coexist. For example, in Somnambules (2009), small figures reminiscent of statues atop columns frame a crudely geometric building, and one seems to hold a showerhead from which grayish-pink water spurts at an impossible angle. It’s hard not to think of Max Ernst in front of some of these constructions, so dreamlike is the architecture. And yet they are entirely drawn. Exquisite corpses, then? But one can see clearly there is only a single hand at work. Hélène Rivière seems fully aware of this play with collage, even to the point of crafting convincingly deceptive “false collages”: the striking HSJEOMRIHNRXEIORUYE (graphite and pastel on paper, 100x65 cm, 2009), shows, against a backdrop evoking soft gray smoke, a frame that appears to be pasted on, where one sees (drawn but clearly after a photograph) elements of a Gothic church interior opening onto a turquoise-blue arch… And yet this addition isn’t pasted but drawn, like the rest.

This dreamlike world is not without a certain sense of illusion. This “elsewhere” is unsettling. Perhaps it is this taste for architectural elements combined with a tendency to create illusions that makes the viewer wonder whether they are really seeing what they think they’re seeing—and which lends certain drawings a theatrical quality. For what is illusory, illusionist architecture, if not a stage set? Some titles are explicit in this regard: Décor misérable (graphite on paper, 42x30 cm, 2008). This particular drawing features what looks like the facades of dilapidated houses opening visibly onto emptiness. ANTI/ITNA (graphite and pastel on paper, 59x42 cm, 2009) presents a strange space (wall, curtain, image of a Greek temple) that, as the title suggests, seems to have no front or back, to be reversible, dismantlable, pure surface, pure image.

This taste for ambiguously defined elements also appears in the faces drawn by Hélène Rivière, which pop up here and there: they tend to merge with masks that sometimes accompany them (Double Je, graphite on paper, 21x29.7 cm, 2008; Missiles et bûches, 42x30 cm, 2008). Rivière indeed uses elliptical, round, and flat shapes for these faces, so they might just as well be paintings, shields, balloons, or children’s toys. Sometimes they’re riddled with arrows, like Saint Sebastians, or stare at us with their colored pupils. We don’t know whether they are characters or objects, silhouettes or symbols. As for the titles, they are cryptic, both in their literal meaning and in their evocative power: Mauvais moment pour les grues (“Bad time for the cranes”), Hutte isolée (“Isolated hut”), Et s’il n’y avait pas d’intérieur (“And if there were no inside”), Paysage aléatoire (“Random landscape”), Somnambules (“Sleepwalkers”), Décor misérable (“Wretched set”), Protection bancale (“Wobbly protection”), Interstices à l’aide (“Interstices to the rescue”), Double Je (“Double I/Game”), Missiles et bûches (“Missiles and logs”)… A world of dreamlike associations, ellipses, and shifts—of images more than statements.

There is in Hélène Rivière’s work a kind of gentle shift away from the expected, a controlled strangeness, an affection for fragile spaces and their tenuous coherence. Her work speaks to us not only of the material fragility of pastel but also of the fragility of constructed spaces and dreamt realities. One feels the desire to build—build with paper and color, with gray graphite and delicate hues. These are not architectural blueprints, nor finished constructions; rather, they are attempts, paper edifices, games of space and sensation, with a careful resistance to fixing meaning, as if each drawing were a piece of memory reimagined, a fleeting architecture.

So yes, perhaps this is where pastel’s unexpected power lies today: in the hands of a young artist who has reclaimed it not to depict likenesses or sentimental scenes, but to explore abstraction, the poetics of space, and the architecture of the imaginary. In Hélène Rivière’s hands, pastel sheds its past and opens into a delicate and subtly disorienting world. A world that is luminous and mysterious.

Text by Emilie Bouvard, April, 2011

Translation: Triangle-Astérides

The portrait of Hélène Rivière was created as part of an invitation to Portraits, la galerie.